Divorce Lawyer & Family Law Attorney Australia: Exploring Legal Support Options

Introduction

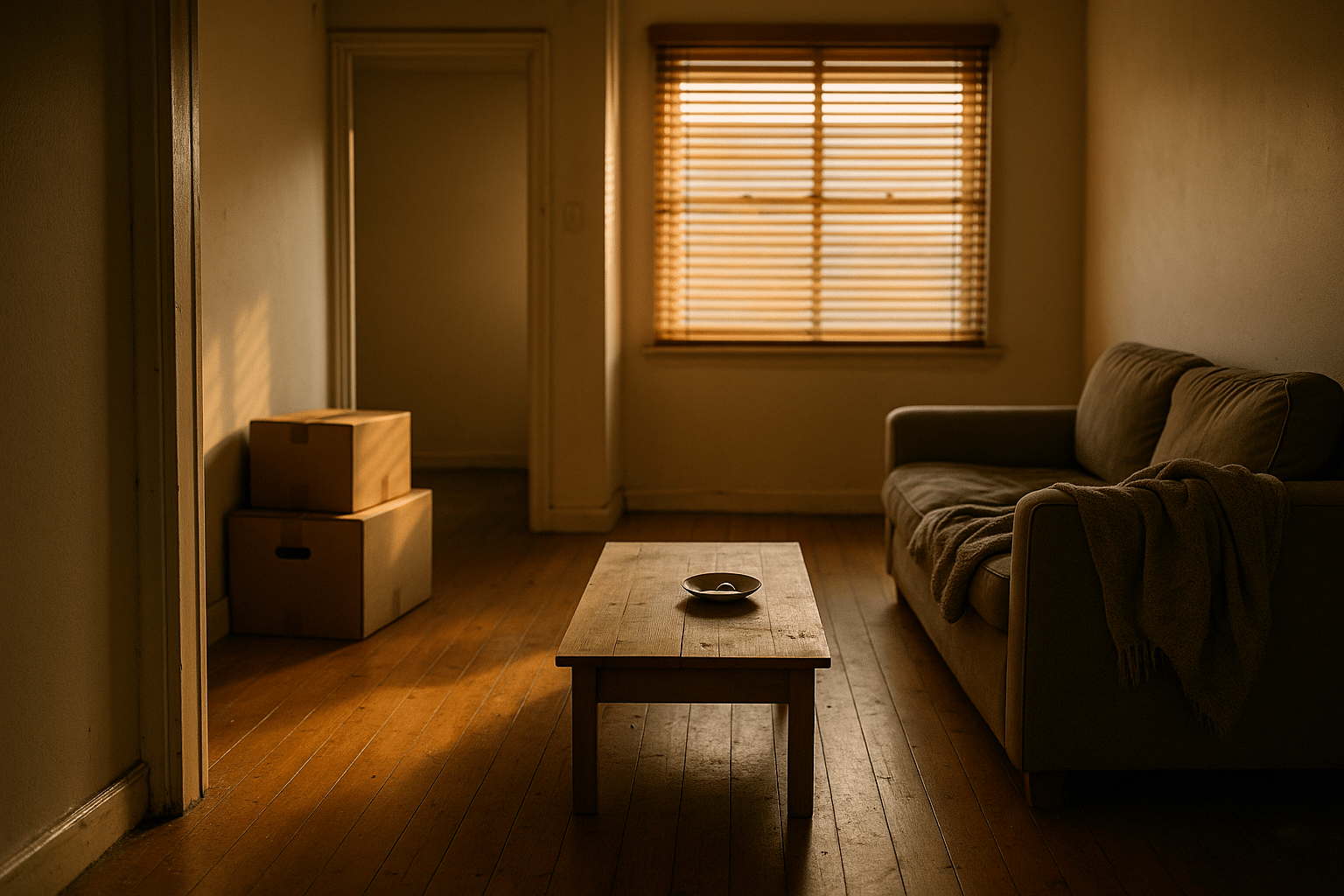

Leaving the family home in the heat of a divorce can feel like the calmest choice in a storm. Yet in Australia, that decision can quietly tilt the legal and financial playing field before anything is settled. This article unpacks why moving out can be a costly misstep, how it affects parenting, property, and cash flow, and what to do instead—especially if safety is an issue. It is general information, not legal advice; always seek independent guidance for your situation.

Outline

1) The legal ripple effects of leaving the home in Australia

2) The financial cost of running two households

3) Parenting arrangements, status quo, and child wellbeing

4) Safer alternatives to moving out (including safety-first pathways)

5) A practical action plan and conclusion for Australian readers

Legal Ripples: How Moving Out Reshapes Your Case in Australia

In Australian family law, where you live during separation can influence the early momentum of your case. Moving out might feel like creating space, but it can also create a “status quo” that courts and practitioners often reference when making interim decisions. While the core test in parenting remains the child’s best interests under federal legislation, the lived pattern of care—who gets kids to school, who attends medical appointments, who provides day‑to‑day structure—can become the foundation of short‑term orders that later shape long‑term outcomes.

Consider the practical effects. If you leave, the other parent may continue the bulk of weekday routines by default. That can look like stability on paper, even if you were equally hands‑on before. Interim hearings tend to value continuity, especially where there’s no immediate risk. If the children are settled in the home with one parent, courts may be reluctant to disturb that arrangement without compelling reasons. Over time, that can reduce your overnight time, affect how quickly you can transition to a 50/50 schedule (if appropriate), and influence recommendations from family reports or expert assessments.

Property and occupation also matter. Remaining in the home doesn’t decide ownership, but it can influence practical control: you have access to records, furnishings, and the day‑to‑day management of an asset in the property pool. If tensions escalate, you can seek “sole use and occupation” on an interim basis, particularly where co‑residence is unsafe or unworkable. Leaving without a plan may weaken your argument for re‑entry, especially if months pass and the other party demonstrates smooth running of the household.

Key risks of moving out too soon include:

– Establishing a new normal that undercuts equal or substantial time in the short term

– Making it harder to gather documents and evidence stored at home

– Ceding practical control over maintenance, access, and inspections

– Inviting disputes about when, how, and whether you can return

None of this means you must stay in a dangerous situation—safety is paramount, and there are protective orders and urgent applications designed for that. But if safety allows, pausing before you hand over the keys can preserve leverage and options you may need in the months ahead.

Money Math: The Hidden Cost of Two Households

Divorce is not only emotional; it is also arithmetic. The moment you move out, you may turn one budget into two. Rent, bond, furniture, utilities, insurance, and travel stack up fast—often before interim maintenance or child support is sorted. Meanwhile, the mortgage and property expenses on the family home continue to accrue, and disagreements over who pays what can rupture negotiations that might otherwise settle early.

Consider a common scenario. One party leaves, takes on a rental at short notice, and buys “just enough” furniture to get by. Within weeks, they’re paying:

– Rent plus bond and connection fees

– Two sets of utilities and internet

– Additional travel for school pick‑ups and changeovers

– Duplicate household goods and unexpected deposits

These costs reduce cash available for lawyers, valuations, and expert reports that can strengthen your case. They also influence property settlement calculations indirectly: while short‑term expenses don’t usually change the size of the asset pool, they affect negotiations and the parties’ appetite for compromise. A strained budget can push you toward hurried deals that are less favourable than what patient, well‑researched bargaining could achieve.

If you stay in the home, even briefly, there are opportunities to structure smarter interim arrangements. You might:

– Document who pays the mortgage, rates, and maintenance pending settlement

– Share in‑home spaces while living separately under one roof (with boundaries)

– Agree on partial offsetting of expenses against eventual settlement

– Use the time to inventory assets, photograph condition, and organise appraisals

When relocation is unavoidable, planning reduces the financial burn. Shop second‑hand, borrow essentials, and prioritise flexible lease terms. Keep receipts and records of all outlays linked to separation. Importantly, set a mediation timeline early so you are not carrying two households longer than necessary. The goal is not to “win” by staying; it is to avoid a cash flow cliff that narrows your legal options and makes early compromises feel like the only workable path.

Parenting, Status Quo, and the Story the Evidence Tells

In parenting matters, facts on the ground often speak louder than intentions. If you move out and your time with the children drops, even temporarily, that reduced pattern can be reflected in affidavits, diaries, and school records. While the law prioritises best interests—safety, meaningful relationships, and practical arrangements—the “story of stability” carries weight, particularly at the interim stage when the court has limited evidence and must avoid disruption without good reason.

Why the status quo matters:

– Children’s routines are central to wellbeing, and courts try to preserve stability

– Interim orders often mirror recent patterns rather than pre‑separation ideals

– Professional recommendations can be influenced by what is currently working

If you remain in the home, it is easier to demonstrate continued involvement in the micro‑tasks of care: managing homework, coordinating extracurriculars, booking medical appointments, and participating in day‑to‑day bedtime and morning routines. Those details become the breadcrumbs that form a persuasive narrative of reliability. If you have already left, you can still build a strong record by showing consistency—on‑time changeovers, attending school events, maintaining a calm tone in communications, and proposing practical solutions.

Communication matters. Use neutral language in messages, confirm agreements in writing, and avoid impulsive changes that can be characterised as instability. If conflict spikes, structured tools and parenting apps (or even a simple email protocol) help reduce escalation and create a clear paper trail. If there are safety concerns, report appropriately and seek protective orders; allegations without evidence can backfire, while documented concerns are taken seriously.

There is also the human side. Children notice who stays steady when their world feels wobbly. Whether you remain in the home or not, the aim is to show you can deliver low‑conflict, predictable care. Moving out can make that harder at first, but not impossible—as long as you act deliberately, document consistently, and prioritise the child’s needs above the urge to “win” a momentary point.

Safer Alternatives: When You Should Leave—and How to Preserve Your Position

Sometimes, leaving is the right call. If you or the children are at risk, safety comes before strategy. Australian law provides pathways for protective orders, urgent parenting directions, and exclusive occupation to keep parties apart. The mistake is not leaving for safety; the mistake is leaving without a plan when it is safe to pause and organise.

Safety‑first pathways include:

– Urgent protective orders and safety planning with support services

– Applications for sole use and occupation where co‑residence is unsafe

– Third‑party temporary stays with clear time‑limited arrangements

– Early legal advice on parenting proposals and evidence needs

If safety allows you to stay briefly, consider “separation under one roof.” It is imperfect, but it can preserve access to documents, maintain involvement in children’s routines, and buy time to craft interim agreements. To make it workable:

– Establish boundaries: separate bedrooms, shared calendar, set quiet hours

– Split bills transparently and record contributions

– Use a written protocol for communication to avoid hallway arguments

– Schedule early mediation so the arrangement has an end point

When moving out is unavoidable for non‑safety reasons—work location, space constraints, or severe conflict—reduce legal and financial downsides with a deliberate checklist:

– Propose a detailed interim parenting plan before you move, including weekdays, handovers, holidays, and communication norms

– Inventory and photograph household contents and important documents

– Set a budget for the second household and favour short leases

– Keep a separation diary noting care tasks, expenses, and interactions

– Book mediation and property valuations within a defined timeline

Creatively, think like a project manager. Your aim is to stabilise the next 90 days so they don’t dictate the next nine years. A calm, documented transition signals to the other side—and to any decision‑maker—that you are focused on the children’s needs, realistic about finances, and ready to negotiate sensibly.

Action Plan and Conclusion: Hold the Keys, Keep Your Options

The moments around separation are a chess opening. One rushed move can concede space you will spend months trying to reclaim. If it is safe, delay moving out until you have a map: a parenting proposal, a budget, a plan for evidence, and a mediation date. If it is not safe, leave promptly and use the legal tools available to protect yourself and the children while preserving your longer‑term position.

A practical, Australia‑focused checklist:

– Decide safety first. If risk exists, act immediately and seek protection

– If safe to stay briefly, consider separation under one roof with clear rules

– Draft an interim parenting schedule in writing before any move

– Inventory assets and collect documents while you have access

– Lock in mediation, valuations, and early legal advice within set timelines

– Track expenses and care tasks; documentation is quiet leverage

– Communicate neutrally and confirm agreements in writing

The bigger picture is leverage and stability. Remaining in the home—where appropriate—can help maintain parenting involvement, ease financial strain, and protect access to information. Moving out without a plan can do the opposite, unintentionally cementing a narrative that is hard to unwind. Your aim is not to “dig in” at all costs; it is to make thoughtful, well‑timed moves that keep options open and encourage settlement on durable terms.

For readers navigating Australian family law, the takeaway is clear: pause, plan, and prioritise safety and evidence. With a steady approach, you can avoid turning an impulsive exit into a long‑term disadvantage—and instead chart a path that balances wellbeing, finances, and fair outcomes for everyone involved.